Briefing

Moscow. Classified research institute. March 2026.

The conference hall was designed for a hundred people, but today perhaps twenty had gathered. They sat in scattered groups, like passengers on a night train who’d randomly ended up in the same car: someone buried in their phone, someone leafing through printed materials stamped “For Official Use,” someone simply staring at the ceiling with the expression of someone torn from important work for yet another bureaucratic whim.

Marina Sergeevna Kozlova, head of the advanced development department from Energia Rocket and Space Corporation, surveyed the hall and caught the eye of a gray-haired man in a chunky-knit sweater. He nodded slightly—she recognized Academician Semenov, a nuclear physicist from the Kurchatov Institute. So she wasn’t the only one who’d received a strange invitation to a “strategic meeting on a project of special importance” without specifying the topic.

Strange company. A young guy by the window—thin, in glasses—was explaining something to his neighbor, jabbing a finger at a tablet screen; fragments about neural networks and some kind of swarm reached Marina. Next to him sat a solid man with a weathered face and hands that knew physical labor. A bit further—a woman in a strict suit, before her a laptop with orbit graphs. By the far wall, arms crossed on his chest, stood a stocky man in a polar jacket—tan eroded by wind, not sun. In the first row, barely fitting in a standard seat, sat a man around thirty-five—huge shoulders, muscle bulges under his jacket, as if he’d come straight from a bodybuilding competition. But something in his calm confidence told Marina: this one’s in charge.

“Excuse me,” Marina addressed her neighbor on the right, a gloomy type in a rumpled jacket, “did they explain anything to you either?”

“‘Invitation to participate in interdepartmental group work,’” he quoted. “And a signature of such level that refusal was impossible.”

Marina nodded. At the entrance each had been given a form—nondisclosure agreement. She’d signed without looking, but now, surveying the hall, she thought: what could be so secret to tell this strange company?

The door opened. Two people entered the hall. Marina expected to see officials or generals, but these two looked completely different.

The elder—an elderly man, short, stocky, with thinning gray hair and attentive eyes behind thin-framed glasses. Old-fashioned jacket, no tie, worn briefcase from which protruded the corner of a blueprint. This is what people look like who’ve spent their whole life building things, not managing those who build.

Next to him—a young man, very young, around twenty-something, thin, with a youthful face. A strict suit sat awkwardly on him, as if he wasn’t yet accustomed to such clothing.

Strange pair.

“My name is Valery Petrovich Goncharenko,” he said without raising his voice. “I’m director of the Institute of Space Problems. You’ve probably not heard of us—we’re a small institute, and that was a conscious decision.” He indicated the young man next to him. “This is Sergei Yuryevich Grishin, head of the analytical department of Vector group.”

Marina noticed how several people in the hall exchanged glances. Vector group was a legend—rumors circulated about it, but no one really knew what it did. And this guy looked about twenty-two, no more.

Goncharenko swept the hall with his gaze, lingering on each face.

“Before we begin, I want to make sure everyone’s here.” He extracted from his briefcase a sheet folded in quarters. “Let’s go in order. Please introduce yourselves.”

“Kozlova Marina Sergeevna, Energia, carriers and orbital assembly.”

“Semenov Alexei Ivanovich, Kurchatov Institute, nuclear energy.”

“Novikov Artem Viktorovich, Skoltech, robotics and neural networks.”

“Orlova Elena Alexandrovna, Sternberg Institute, orbital mechanics and ballistics.”

“Volkov Dmitry Sergeevich, NPO Lavochkin, spacecraft.”

“Fedorov Mikhail Alexandrovich, VIAM, materials science.”

“Morozov Igor Petrovich, Arctic Institute, autonomous systems in extreme conditions.”

Goncharenko folded the list.

“I understand you were torn from your usual work without explanations. This was necessary. What you’re about to hear is classified, and I ask you to take this seriously.”

Pause. Marina noticed how a wave ran through the hall—people straightened, set aside phones.

“You’re being asked to build a system that will change human civilization,” Valery Petrovich continued. “Not improve. Not modernize. Change—as radically as fire or electricity changed it.”

Someone chuckled. Valery Petrovich nodded:

“Yes, I know how that sounds. But let me explain what we’re talking about.”

He held the pause.

“The goal—to catch the Sun.”

Several people exchanged glances.

“We’ll build the first automatic factories on Mercury. These factories will build new factories, robots, mass drivers, and mirrors. Hundreds of millions of mirrors. Mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults—will shoot mirrors into space, and together they’ll form a Swarm that will intercept one percent of solar energy and direct it to Earth.”

He swept the hall with his gaze.

“One percent. That’s enough to cover all of humanity’s energy needs. Forever. Free electricity for every country, every village, every home. Ocean desalination so deserts bloom. Fuel synthesis for aircraft. Carbon dioxide processing. The end of energy poverty.”

Silence. Then Fedorov said quietly:

“Sounds like a fairy tale.”

“A fairy tale is when no one knows how,” Valery Petrovich smiled slightly. “And we have blueprints. I’ll show you today. Let’s start with the place where all this will happen.”

The screen behind Valery Petrovich came alive, showing a gray, crater-pocked surface. Mercury—the planet closest to the Sun.

“The first question you’ll ask: how to build a factory in hell?” Valery Petrovich brought up a list on screen. “Vacuum. Temperature swings from plus four hundred thirty to minus one hundred eighty degrees. Abrasive dust charged with static electricity. Radiation.”

He paused.

“If you try to unload an ordinary machine tool there, it’ll die in an hour. Lubrication will evaporate. Metals will cold-weld on contact. Thermal fatigue will destroy bearings.”

Semenov nodded—this was his territory, extreme environments.

“The solution is called ‘Cocoon,’” Valery Petrovich switched slides. A 3D model appeared on screen: a multilayered dome on the planet’s surface. “We’re not building a factory on Mercury. We’re bringing it with us, packaged in a hermetic cocoon.”

The model rotated, showing a cross-section. Outer shell, thermal insulation, internal environment.

“Kevlar dome. Folded it occupies half a cargo bay, but when inflated with technical gas it becomes a shop floor of five hundred square meters. Inside—pressure one-tenth atmosphere. That’s enough for mechanisms to live: gas creates an environment where liquid lubrication works, there’s convection for heat removal, metals oxidize and don’t cold-weld on contact. An oasis in the middle of cosmic desert.”

Valery Petrovich switched slides. A solar furnace: a huge mirror focusing light to a point.

“And outside—vacuum. And vacuum is our friend. On Earth, to melt metal, we spend gigawatts of electricity or burn tons of coal. On Mercury solar flux is nine kilowatts per square meter, six to seven times more than in Earth orbit. At first, while there are no mirrors, we melt with electricity—solar panels on Mercury produce enormous power. But as soon as the factory produces first mirrors, we switch to solar furnaces: mirror focuses light directly into crucible—two thousand degrees without a single watt of electricity. Heat losses practically zero: in vacuum there’s no convection, heat leaves only by radiation.”

He brought up a periodic table on screen.

“Resources. Mercury is an anomalous planet. Giant metallic core, only lightly dusted with rocky crust. Iron—seventy percent. Silicon—twenty percent. Aluminum, magnesium, titanium—sufficient. Almost no carbon—no plastics, rubber, oils. But we don’t need them in large quantities. We bring from Earth only what’s impossible to make on site: electronics, optics, precision mechanics. We call this ‘vitamins’—one percent of mass. The other ninety-nine percent—from local raw materials. For every kilogram of cargo from Earth—one hundred kilograms of finished equipment.”

Valery Petrovich paused.

“But we won’t fly to Mercury right away.”

He switched slides. The Moon appeared on screen—a familiar gray disk with dark seas.

“First—the Moon. Test site. We’ll work everything out here, one and a half light-seconds from Earth, before flying a hundred million kilometers.”

A comparative table appeared on screen.

“The Moon is different. Iron in the crust only ten percent versus seventy on Mercury. Silicon and aluminum—more.”

“Wait,” Semenov interrupted. “On the Moon solar flux is six times weaker than on Mercury. Did you think about this? Solar furnaces will work completely differently there.”

Goncharenko nodded to Grishin. He stood.

“We calculated this.” His voice was unexpectedly confident for his age. “Yes, six times less sun. Seven times less iron. In sum—production will be thirty to forty times slower than on Mercury.”

He paused, letting the numbers settle.

“But we don’t need speed. The Moon is a test bench. We’re not chasing a hundred-to-one ratio. Ten-to-one is enough. We can afford to bring more from Earth, stop production during lunar night. The main thing—prove the system works. And if we need continuous cycle—Rosatom already has a joint project with China for a lunar reactor for thirty-three to thirty-five. Power—up to ten megawatts. We’ll just accelerate these plans.”

Semenov nodded.

“Confirmed. Kurchatov Institute participates in the project.”

Grishin sat back down. Goncharenko continued:

“And the Moon’s main advantage—near-real-time communication. If something goes wrong, we’ll know in a second, not five to ten minutes. We can intervene, correct, reprogram. Moon—our test bench. Mercury—the goal.”

“Now—robots.” Valery Petrovich switched slides. Four silhouettes appeared on screen: something like a spider, a portal crane on wheels, a machine with manipulators, and a squat bulldozer. “These aren’t androids from fiction. These are specialized work machines, each for its task. I’ll show each in detail now, but first—the big picture.”

Artem raised his hand.

“You’re showing four types. How many total units needed for start?”

“Fifty-six.” Valery Petrovich brought up a table. “Sixteen spiders, twelve crabs, twenty-four centaurs, four moles. This is the assembly crew—special forces that build the first factory.”

“Fifty-six robots,” Fedorov repeated. “And who repairs them when they break?”

“No one.” Valery Petrovich met his gaze. “They’re disposable.”

Silence.

“These are First Generation robots. Assembled on Earth from the best materials—titanium, carbon, kevlar. Mass-optimized for launch. Expensive, precise, fragile. Designed to work in vacuum until protective dome is built.”

He paused.

“Their task—build the factory in seven days. After that their resource is exhausted. We don’t repair them. Because then the factory starts printing Second Generation.”

The screen split in half. On the left—an elegant robot in white ceramic plates and gold foil, like NASA satellites. On the right—a crude hexagonal body of unpainted steel with visible weld seams.

“First Generation—titanium, ceramics, carbon.” Valery Petrovich pointed left, then right. “Second Generation—steel, cast iron, aluminum. On Mercury we make from what’s available.”

Semenov raised his hand.

“What about motors? Batteries?”

“All robots use brushless electric motors,” Valery Petrovich answered. “First Generation uses solid-state lithium batteries—without liquid electrolyte that could freeze or boil—copper windings, neodymium magnets. Compact, efficient, expensive. Second Generation—sodium-sulfur batteries we produce on site. Sulfur is a byproduct of ore processing, sodium extracted from regolith. Aluminum windings instead of copper, ferrite magnets instead of neodymium—heavier, but all from local materials. Motor controllers—part of ‘vitamins.’”

On screen appeared Spider-E—a six-legged creature of white ceramics and titanium, its joints hidden under golden thermal insulation bellows, as if the robot had borrowed its wardrobe from NASA satellites. Four pairs of stereo cameras behind sapphire glass looked at the hall with the cold curiosity of an insect, and on its back, like a climber’s backpack, was attached a spool with five hundred meters of power cable.

“Eighty-two kilograms on Earth,” Valery Petrovich said. “Thirty-one on Mercury. Tungsten carbide claws with micro-plasma drill in each paw. It scrambles up sheer cliffs no human foot will ever touch, dragging cable behind and deploying solar towers on peaks of eternal light. We have sixteen of these—we expect losses.”

He paused.

“We won’t produce Spiders on Mercury. They’re only needed at initial stage—drag cables up cliffs, deploy towers. Then sixteen units suffice for the entire project: inspection, communication relay, minor repairs at height. We’ll mass-produce Crabs and Moles—those needed constantly.”

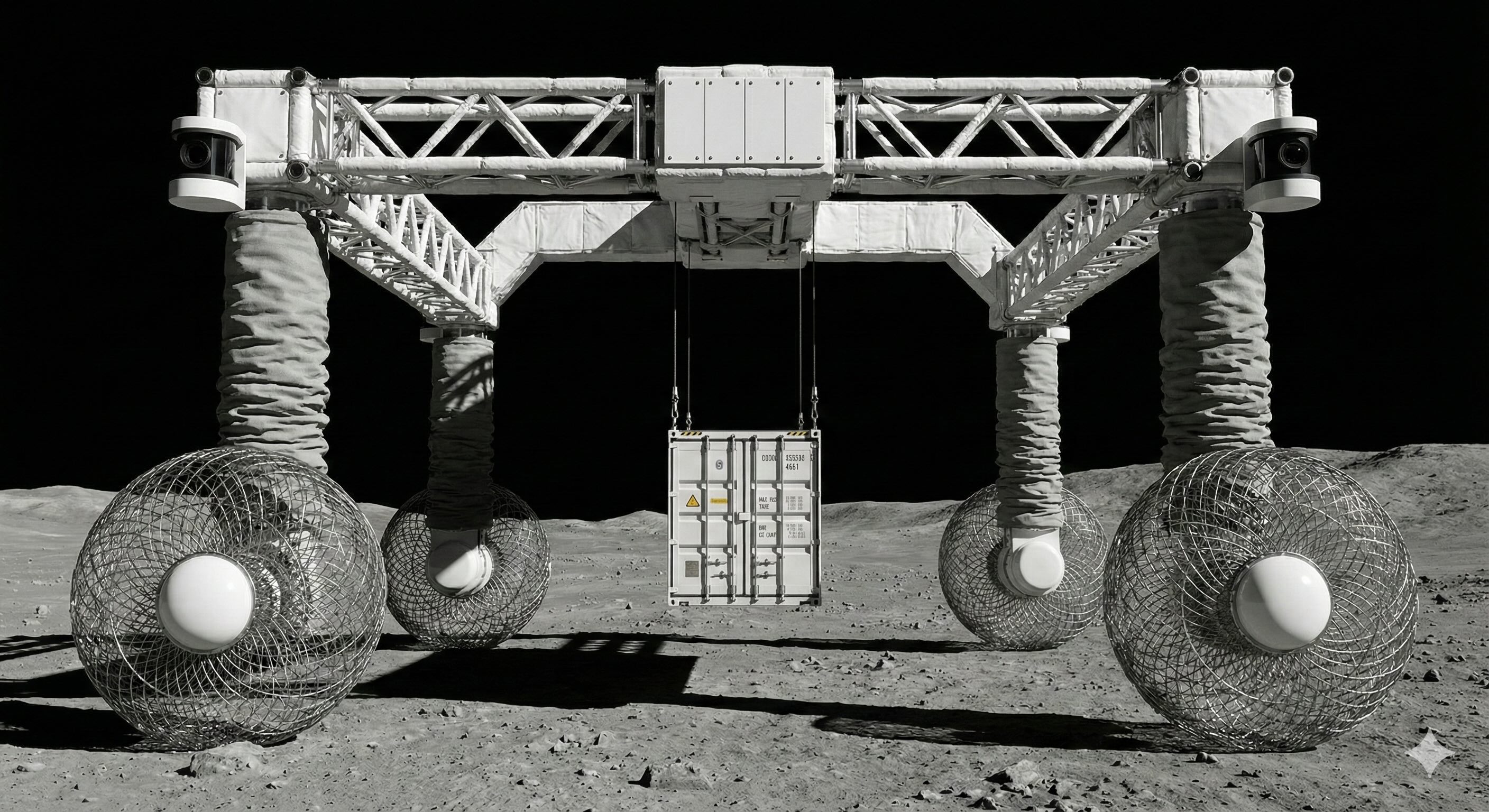

He switched slides, and on screen appeared the bulk of Crab-E—a U-shaped truss arch on four wheels, each taller than a human. The structure resembled a portal crane crossed with a Mars rover: lacy but powerful frame of aluminum tubes in white thermal blankets, airless mesh wheels of gleaming spring steel, telescopic legs hidden under gray kevlar accordion folds.

“Load capacity—up to ten tons,” Valery Petrovich continued. “Crab drives over cargo, lifts it with winches and hauls it. Module unloading from ship, site clearing, logistics—all on it.”

The third slide showed Centaur-E—a six-wheeled rover with humanoid torso crowned by a camera block on an extendable rod. Two manipulator arms, completely enclosed in gray inflated sleeves of Teflon fabric, gave it resemblance to a deep-sea diver. It looked almost friendly—as friendly as a machine created to work in hell can look.

“Centaur is our hands and eyes,” Valery Petrovich said. “Seven degrees of freedom in each manipulator. It turns bolts, connects connectors, welds seams. Algorithms learn from each operation, constantly improve. By landing on Mercury the system will be fully autonomous.”

He paused.

“Each factory needs at least one Centaur—to assemble robots, load the mass driver. Twenty-four units from Earth won’t suffice. So we’ll produce a simplified version—Centaur-M. Cruder, heavier, but it manages.”

The last robot in the gallery was squat and wide, like a bulldozer: tracked platform with skeletal treads, armored cast-iron body barely over a meter tall, and a huge blade in front—three and a half meters of steel polished by friction.

“Mole-M,” Valery Petrovich introduced. “Miner. Gnaws soil and feeds it on conveyor to furnace. One ton weight, of which only ten kilograms—import from Earth. Everything else—local iron and cast iron. Simple, reliable, mass-produced. We’ll have thousands of these.”

He turned off the robot gallery and brought up a new slide on screen—a diagram resembling a city plan, aerial view.

“Now—where all this happens.”

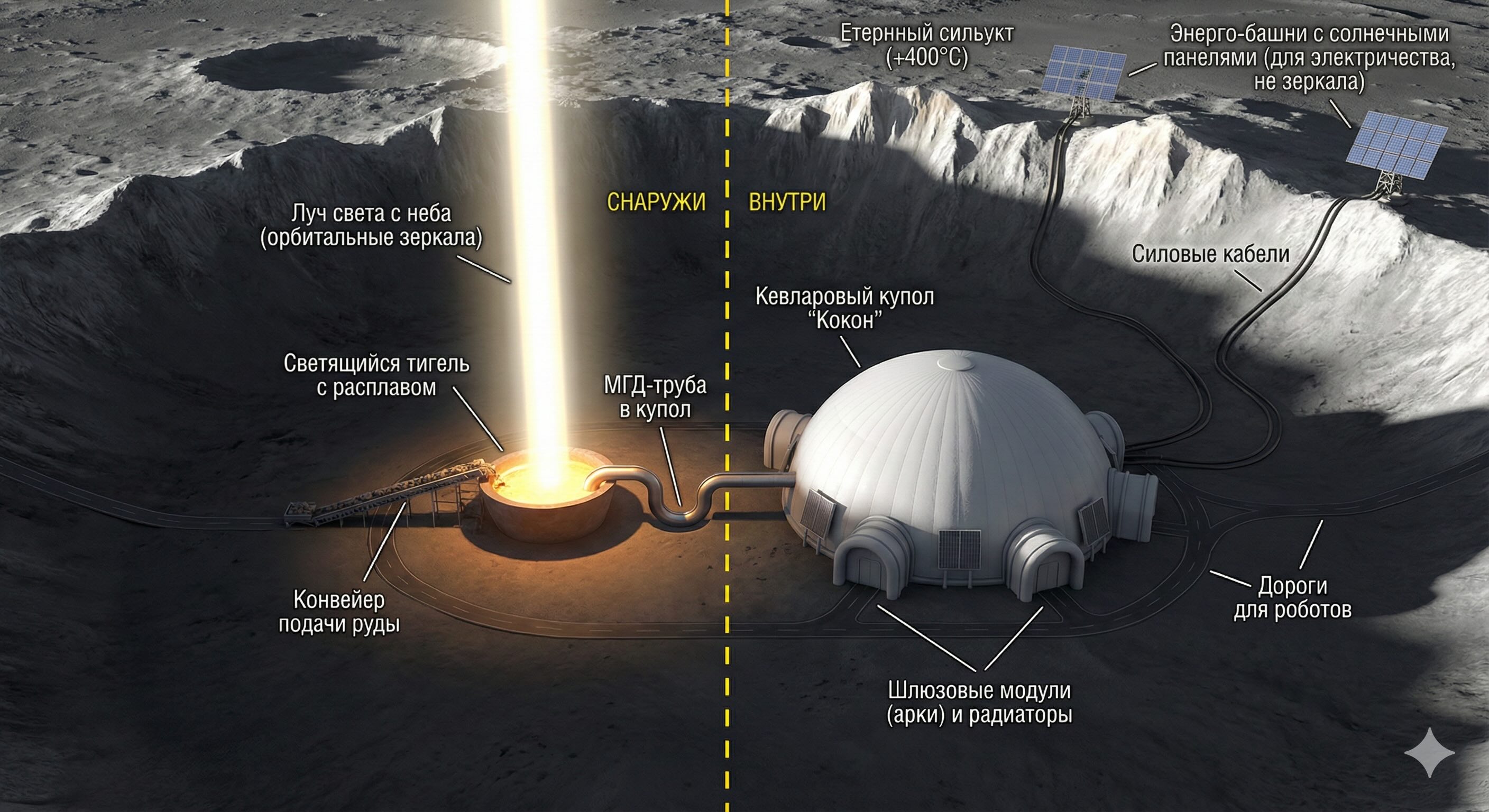

On screen unfolded Prokofiev crater—aerial view, quite large. Near the crater’s edge stood a factory: white inflatable Cocoon dome, glowing crucible of smelter with light beam from orbit, MHD tube from crucible to dome. Two thick cables descended from solar panels on crater ridges.

“Factory ‘Ground Zero,’” Valery Petrovich said. “First production cell. Watch carefully: outside and inside—two different worlds.”

He indicated the area beyond the dome.

“Here—hell. Vacuum, radiation, temperature swings of six hundred degrees. But here’s where the most important thing happens: smelting. Solar furnace concentrates light directly in crucible, melting metal. Electrolyzer separates melt into components: iron settles down, aluminum slag floats up, oxygen bubbles at anode and liquefies into tanks.”

He traced his finger along the tube leading to the dome.

“And here’s the trick. How to transfer molten metal at fifteen hundred degrees through a wall without losing atmosphere?”

“Airlock?” Artem suggested.

“Too slow. We’ll use MHD pump—magnetohydrodynamic input. Sandwich tube of ceramics and inductors. Magnetic field pushes melt like blood through an artery. Plug of the metal itself ensures hermetic seal. U-shaped liquid seal at bottom—additional insurance.”

The screen switched to cross-section—side view showing dome internals and external structures simultaneously.

“Inside—civilization. Nitrogen atmosphere, one-tenth Earth pressure. Enough for lubrication, convection, normal mechanism operation.”

Valery Petrovich began moving the pointer across the diagram.

“Melt enters tundish—buffer vessel for two to three tons. From there—to continuous casting machine: copper crystallizer pulls out blank. Further—rolling mill: stands turn blank into sheets and plates for bodies, into rod for axles and shafts. Drawing mill—rod into wire for welding. Cutting, bending, welding—and basic parts ready. For small complex elements—3D printing: robot manipulator melts wire with arc and builds up part layer by layer. Milling for precision surfaces. And finally—assembly jig: steel skeleton, battery from local sodium and sulfur, ‘vitamins’ from Earth—and in forty-eight hours a new robot drives out of airlock.”

Nearly closed cycle. One percent mass—import. But this one percent turns into one hundred percent finished equipment.

Valery Petrovich switched slides, and on screen appeared something resembling railroad track stretching to horizon—only instead of rails were rows of electromagnetic coils, and instead of train—a streamlined capsule with something rolled inside.

“Everything I showed—robots, factory, production cycle—is infrastructure. Preparation. Here’s what all this is built for.”

“Mass driver. Electromagnetic catapult several kilometers long. Cargo accelerates to four point three kilometers per second—Mercury’s escape velocity—and goes into space. No fuel, no rockets. Only electricity from our solar towers.”

He showed animation: capsule glides along guides, coils flash one after another, accelerating it faster and faster—and finally it breaks from edge of platform and goes into black sky.

“What do we launch? Mirrors. Rolling mill gives us not only wire for robots, but thin aluminum foil. One hundred by one hundred meters, thickness—fractions of a millimeter. Rolled—a roll that fits in capsule size of refrigerator. Every two hours—new launch. In orbit capsule opens, mirror unfolds, begins rotating—and becomes part of Swarm.”

Centaurs load capsules. Crabs deliver rolls from assembly shop. Sensors on guides monitor wear. Conveyor works twenty-four hours a day.

Valery Petrovich paused.

“One factory—six hundred mirrors per day. Thousand factories—two hundred million mirrors per year. Energy—hundred times more than entire world consumes.”

The silence in the hall became tangible.

Marina raised her hand.

“Valery Petrovich, seven days—is that with margin or tight? What happens if we don’t make it?”

“Tight.” Valery Petrovich switched the slide to a graph. “First Generation robots die. Resource in vacuum is limited. Titanium is strong but brittle under thermal cycling. Kevlar degrades from radiation. The longer assembly—the higher risk the crew fails before factory launches.”

He swept the hall with his gaze.

“Imagine landing not as parade but as anthill. Hatches open. First the nimble Spiders tumble out with cable spools and run up crater slopes—every hour counts, robots are dying. Then heavy Crabs crawl out, dragging bales with inflatable dome. Centaurs bustle around, connecting hoses and cables. All this happens in absolute vacuum silence, under harsh starlight.”

“Seven days,” he repeated after a pause. “On the seventh—first Second Generation robot drives out of airlock. From this moment factory begins reproducing itself.”

On screen appeared a curve rising almost vertically. “And here’s where magic begins. Exponential growth.” Valery Petrovich pointed to the graph’s beginning: “Six months—one factory, one mass driver, one hundred robots. By year’s end—ten mass drivers, because factories also build factories.” He traced his finger further along the curve. “Eighteen months—ten. Three years—hundred. Four years—thousand mass drivers, twenty thousand robots. By this point we’re already producing a hundred times more energy than the entire world consumes. And here exponential ends.” He stopped. “We switch to maintenance mode. Goal achieved.”

Several seconds no one spoke. “Thousand,” Semenov repeated quietly. “Not million?”

“Not million.” Valery Petrovich smiled. “I also initially dreamed of millions. But my young colleague,” he nodded at Grishin, “explained that exponential is a tool, not a goal. We don’t need to cover all Mercury with factories. We need to solve Earth’s energy problem. Thousand mass drivers—sufficient.”

He turned off projector. Screen went dark.

“Questions?”

Hands rose almost simultaneously. Valery Petrovich nodded to Artem.

“Control. How are you going to coordinate twenty thousand autonomous units? That’s a logistical nightmare.”

“You’ll answer this question better than me.” Valery Petrovich spread his hands. “I’m confident several approaches exist. Our task—choose most reliable and implementable. The only thing I know for sure: signal from Earth to Mercury takes four to twelve minutes, so direct control is impossible. System must be autonomous.”

Marina raised her hand.

“Failures. In any system something breaks. What happens when a thousand robots break simultaneously?”

“Nothing catastrophic.” Valery Petrovich shrugged. “Broken robot is just raw material. A working one picks it up, hauls to furnace, remelts into new parts. Closed cycle. Only ‘vitamins’ are consumed, and we deliver them.”

Fedorov didn’t raise his hand—just spoke:

“I’ve been in production thirty years. Never saw a system without humans that worked longer than a month. Always somewhere someone must tighten a nut, notice tremor in machine, make decision that doesn’t fit algorithm.”

Valery Petrovich shook his head. “By landing on Mercury we’ll pass two stages: training on Earth in simulators and real tests on Moon. Each error, each abnormal decision—is training example for neural network. By Mercury algorithms will be trained on millions of hours of real work. We expect system will be fully autonomous from day one. And remote connection via VR—only for exceptional cases when something goes completely wrong.”

Semenov raised his hand.

“Coronal mass ejections. At that orbit electronics will get full dose. Are you building in redundancy?”

“Absolutely,” Valery Petrovich nodded. “Critical nodes tripled. Plus passive protection: sensitive electronics hides inside steel bodies that shield from protons. And solar activity sensors will give warning hours ahead—robots will have time to retreat to crater shadow.”

Marina raised her hand.

“Valery Petrovich. How much time needed to build this?”

“From first landing to Swarm reaching full power—on paper ten years. In fact, more likely fifteen.” He folded his arms on his chest. “I understand that sounds like eternity. But China built Three Gorges in seventeen years. We built BAM in twenty. This is comparable. Except prize at end isn’t dam or railroad.”

He took a step toward the hall.

“We must jointly develop this project and present it to international consortium. Russia won’t build this alone—the project is too large. Robotics, metallurgy, astronautics, energy, materials science—all this must be coordinated with partners. What you saw today—is our vision. But you’re experts, you know better how this should actually work.”

The muscle-bound guy from the first row—the one Marina had taken for the boss—rose from his seat.

“Pavel Dostochkin, Vector group,” he introduced himself. “We work jointly with Administration on project’s operational part. Your task—confirm that fundamental development makes sense, clarify details and help prepare materials for discussion with foreign partners. We have a month. Not six months, not a year. A month.” He swept the hall with his gaze. “This is highest priority project. I don’t know what you’re currently working on, and I’m not interested. But if you have to choose between your current projects and this—choice already made for you.” He paused. “On organization. You’ll receive materials tonight on secure email—each will have access to common database and your section. Physics questions—to Valery Petrovich, robotics—to Artem Novikov, he agreed to coordinate this direction. Weekly calls on Wednesdays, report format—free, main thing—specifics. What’s unclear, what doesn’t add up, what needs recalculation.”

He paused.

“Questions?”

Hands rose in several places simultaneously, but no one waited for formal answer—hall already filled with hum of voices. People stood, changed seats, gathered in groups—not by rows but by interests. By the window Fedorov waved his arms, explaining something about thermal cycling; Elena from Sternberg talked with Volkov from NPO Lavochkin—two spacecraft specialists found each other instantly. Someone drew diagrams on the board, someone leafed through materials on laptop. By the stage around Goncharenko and Grishin a group gathered—Marina saw Artem and Semenov approach them and animatedly ask professor something while Grishin scrolled through something on tablet.

Dostochkin stood by door, swept the hall with his gaze—arguing, drawing, bent over screens. Nodded with satisfaction and left.