Prologue

October 14, 2075. “New Yakutia” Agglomeration, “Aldan” Reception Sector.

You ask me what the old world was like. You read textbooks, watch holograms in the archives, see graphs of the “Great Transition”—but you don’t understand. For you, energy is like air. You don’t think about it when you breathe. It doesn’t occur to you that you could receive bills for air. That people could kill for air.

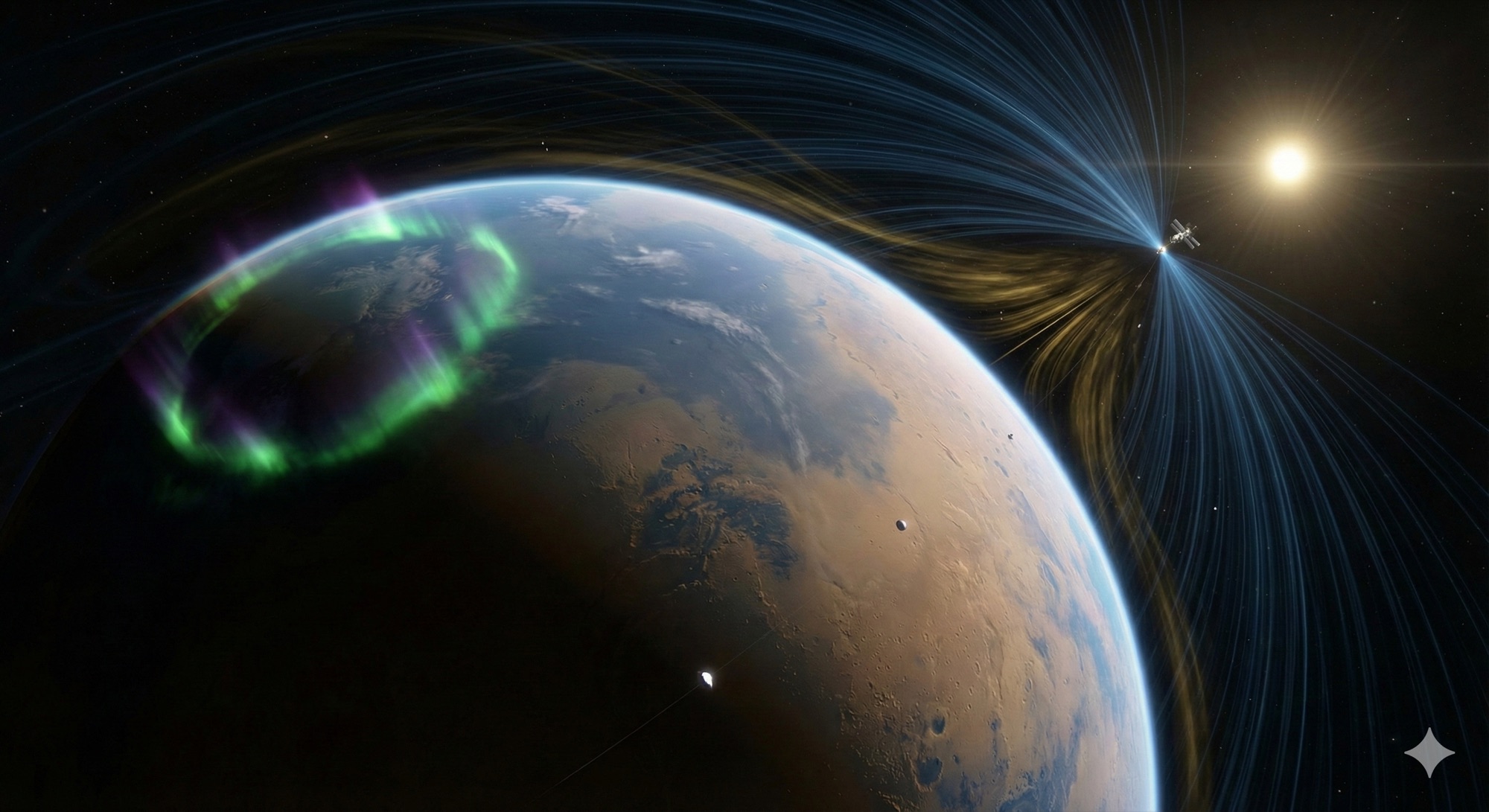

Look out the window, Boris. Beyond the dome’s glass—minus forty degrees, a blizzard burying the old cedars. But here, inside, peach trees bloom. Look higher. See that? Through the leaden clouds pierces a perfectly straight, blindingly white column of light. It doesn’t tremble. It doesn’t fade. The clouds around it don’t simply part—they evaporate instantly, forming a perfect ring of clear sky a kilometer in diameter. We call it the “Eye of the Storm.”

That’s the Laser Corridor. It strikes from orbit, piercing the atmosphere like a white-hot needle through butter. You live in a world where the word “conservation” has become an archaism. If you need water—you desalinate the ocean. If you need aluminum—you take clay from beneath your feet and run it through electrolysis. If the weather’s bad—you feed more power to the dispersal lasers, and the clouds above the city vanish in seconds. The price per kilowatt—zero.

But I remember a time when we counted every joule. I remember 2026. I was thirty. I was a young engineer who had just defended his dissertation. We lived in a state of quiet hysteria—they told us to turn off taps, switch off lights, switch to electric cars we had nowhere to charge. We called it the “green transition,” but it was like trying to patch the Titanic’s hull breach with postage stamps. We fought over oil, Borya. Can you imagine? We burned black sludge pumped from the earth to keep warm, and choked on the smoke. We killed each other for the right to lay a pipeline across someone else’s border. That was the world of Scarcity. A world where development hit a glass ceiling. We wanted to fly to Mars but couldn’t afford the fuel. And then we looked up. And decided to pull off the most audacious heist in the history of the Universe.

We decided to steal a star.

Don’t think it was beautiful. It wasn’t like those glossy pictures hanging in your school. It was dirty. It was frightening. It was painful. When the first robots began dismantling Mercury, people on Earth protested, seeing it as violence against the cosmos—and they were partly right. When we poured concrete over Siberian taiga and the Gobi Desert to build giant photoreceptor dishes, they called us madmen. We created the “Silicon Famine” of the forties. We scraped up every reserve of quartz and rare earth metals on the planet to create mirrors and photovoltaic cells capable of withstanding a laser strike of such power. But we built it.

You know what Mercury looks like now? If you look through a telescope—you won’t see a dead rock. You’ll see an industrial planet. The entire surface is covered with factories, conveyor belts, mass drivers. They work continuously, spitting mirrors into orbit. We didn’t dismantle it—we transformed it into a machine. A living, self-reproducing factory the size of a planet. Cruel? Yes. But look at Earth. Look at the Sahara—the former desert now produces a third of the planet’s food supply. The water there is desalinated, pumped in by systems powered by “Helios.” Look at the trash—there is none. Plasma incinerators break down any garbage into atoms.

And you know what’s amazing? Mars. When I was young, a flight there was a madman’s dream. Fuel cost more than the entire mission. Now two hundred thousand people live there. We covered the planet with a magnetic shield so solar wind wouldn’t strip away the atmosphere. Fifteen years—and the air became dense enough to walk in a mask, not a spacesuit.

Three years ago, the first lake appeared. Liquid water, flowing, under open sky. I remember watching the broadcast—scientists stood on the shore and wept. Children were born there. The first Martian generation. They look at Earth through telescopes and don’t understand why our sky is blue. That’s what a foundation gives you. We stopped struggling for survival on one planet—and began to grow.

We didn’t build paradise, Borya. People remained people. We still have corruption, crime. We argue about how much heat we can dump into the atmosphere without overheating the planet with our endless lasers. But don’t believe those who say abundance made us weak. That’s a lie. We did what we dreamed of for thousands of years: we closed the base of Maslow’s pyramid. Fed and warmed everyone. And you know what happened? Humanity didn’t fall asleep. On the contrary. Freed from the rat race for a crust of bread, we felt a new, real hunger—hunger for achievement. We stopped fearing tomorrow and started engineering it. We now have a Foundation.

I’m writing this letter because I feel my generation is leaving. We are those who remember the Darkness. Those who built the Bridge. Protect it. Not from fear that we’ll return to caves—we’re humans, we’ll survive anywhere. But why crawl when we’ve learned to fly? This Beam is our springboard.

There’s an old idea, Borya. They say the Universe created humanity for one purpose—to know itself. For billions of years it was enormous, blind, and mute. And then we appeared. We are its eyes. We are its mind. While we fought for warmth and food, we had no strength for this work. We were too busy surviving. But this Beam finally allowed us to do our main job. To look. To study. To understand.

Your father said you’re going for an internship at the Orbital Shipyards? They’re starting construction on a ship to Jupiter. Antimatter-powered. We once considered this fantasy. And now—just a question of logistics. All you need is energy. And now we have an entire Sun. Fly, Borya. Look. Understand. Conquer. That’s your job now.

— Your grandfather, Viktor

Viktor Goncharenko, Honorary Chief Engineer of “Helios-Eurasia”